-

"الفلك الموضعي"

- مقدمة

- الكرة الأرضية

- هندسة المثلثات الكروية

- ملاحظات حول الهندسة الكروية

- إحداثيات أفقية "alt-az"

- إحداثيات استوائية "HA-dec"

- إحداثيات استوائية "RA-dec"

- الزمن النجمي

- الانتقال بين أفقي و استوائي

- إحداثيات مجرية

- إحداثيات بروجية

- الانتقال بين بروجي و استوائي

- حركة الشمس و ضبط الوقت

- القمر

- الإنكسار الجوي

- شروق و غروب الشمس، الشفق

- اختلاف المنظر المركزي اليومي

- اختلاف المنظر الموسمي

- الزيغ

- المبادرة و الترنح :اضطراب محور الأرض

- تقاويم

- الامتحان الأخير

- الإحداثيات الفلكية، خضر الأحمد

- الحركة الظاهرية للنجوم (تفاعلي)

- الأقطاب السماوية (تفاعلي)

الهندسة الكروية

يناظر قوس الدائرة الكبرى على سطح الكرة و يماثل الخط المستقيم في المستوي.

و بتقاطع اثنين من هذه الأقواس, نستطيع تعريف الزاوية الكروية و كذلكالزاوية بين مماسي القوسين عند نقطة التقاطع, أو الزاوية بين مستويي الدائرتين الكبيرتين عند تقاطعهما في مركز الكرة. (تعرف الزاوية الكروية فقط في نقاط التقاء أقواس الدوائر الكبيرة .)

يتألف المثلث الكروي من ثلاثة أقواس لدوائر كبرى, مجموعها كلها أقل من 180°. إن مجموع الزوايا غير ثابت, و لكنه دائماً هو أكبر من 180°. و يدعى المثلث الذي يمتلك قيمة 90° لأحدى زواياه; quadrantal.

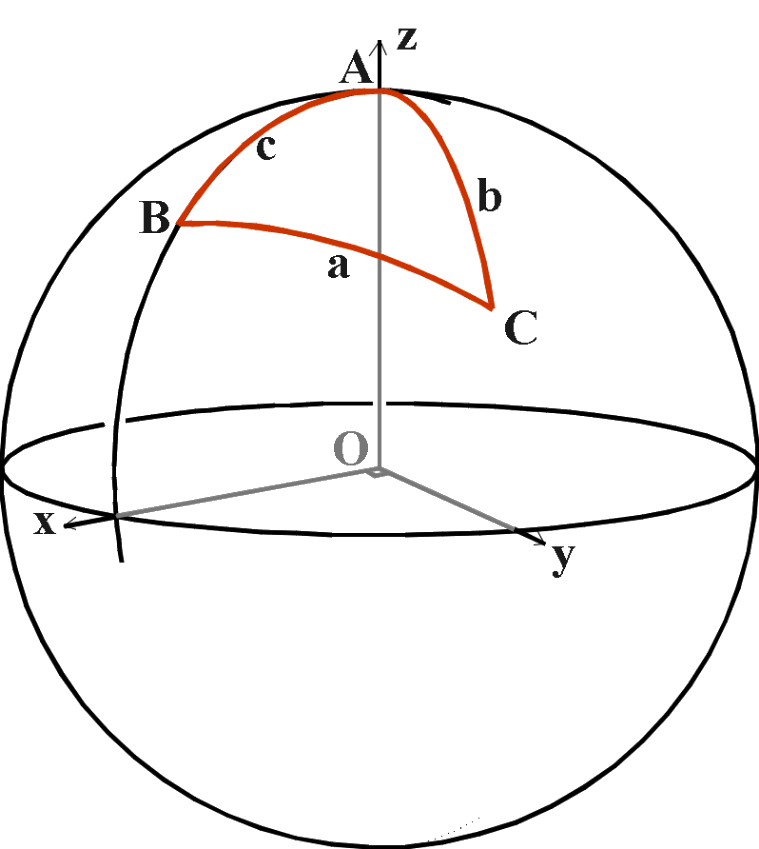

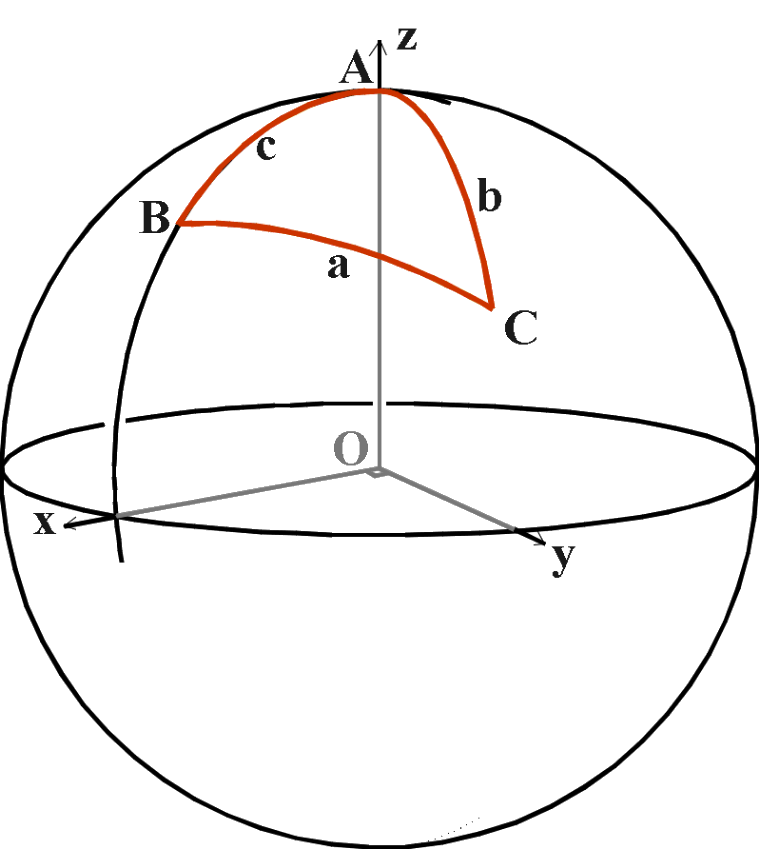

(الشكل-9) المثلث الكروي

(الشكل-9) المثلث الكروي

يوجد العديد من الصيغ الرياضية المتعلقة بزوايا و أطراف المثلث الكروي. و سوف نستخدم في هذا الكورس صيغتين فقط : صيغة الجيب و جيب التمام.

(الشكل-10) المثلث الكروي في إحداثيات XYZ

(الشكل-10) المثلث الكروي في إحداثيات XYZ

سنفترض المثلث ABC على سطح كرة قطرها = 1.

(See ملاحظات حول الهندسة الكروية)

نستخدم الحروف الكبيرة A, B, C للإشارة إلى الزوايا ; في الوقت الذي تستخدم رموز الأحرف الصغيرة a, b, c للإشارة إلى الأقواس المقابلة للزوايا. (تذكر دائماً, إن أطراف المثلث في الهندسة الكروية هي أقواس دوائر كبرى, و بالتالي فهي أيضاً تعتبر زوايا.)

قم بتدوير الكرة بحيث تضع النقطة A عند "القطب الشمالي", و سوف نعتبر القوس AB تعريفاً "للزوال الرئيسي".

نفترض الآن نظام إحداثيات متعامد OXYZ: حيث تقع O في مركز الكرة; و يمر الخط OZ عبر النقطة A; المستوي OX يمر عبر القوس AB (أو عبر امتداده); المستوي OY معامد لكلا المستويين السابقين. و في نظامنا الإحداثي هذا فإن إحداثيات النقطة C :

y = sin(b) sin(A)

z = cos(b)

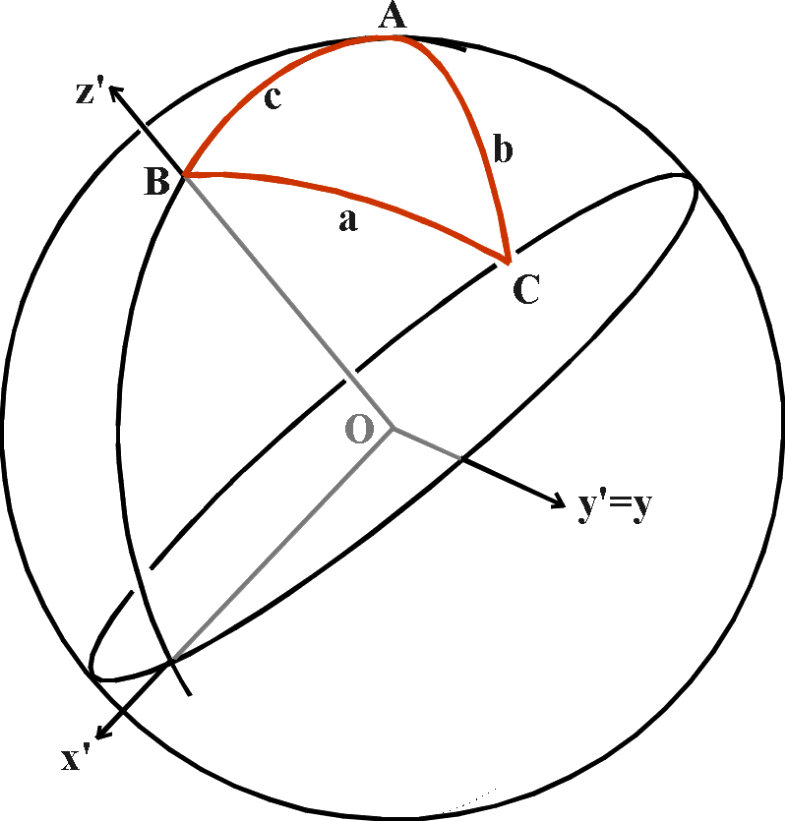

(الشكل-11) المثلث الكروي في إحداثيات جديدة بعد عملية الدوران

(الشكل-11) المثلث الكروي في إحداثيات جديدة بعد عملية الدوران

و الآن لنقم بإنشاء مجموعة إحداثية جديدة, مع ترك المحور y ثابتاً و تحريك "القطب" من النقطة A إلى النقطة B ( بما يعني تدوير المستوي x,yعبر الزاوية c). و تكون الإحداثيات الجديدة ل C هي كالتالي:

y' = sin(a) sin(180-B) = sin(a) sin(B)

z' = cos(a)

و ببساطة فإن العلاقة بين الإحداثيات القديمة و الجديدة هي دوران للمحاور x,z عبر الزاوية c :

y' = y

z' = x sin(c) + z cos(c)

و بالتالي نحصل على الصيغ التالية :

sin(a) sin(B) = sin(b) sin(A)

cos(a) = sin(b) cos(A) sin(c) + cos(b) cos(c)

هذه المعادلات تعطينا الصيغ القادرة على حل المثلثات الكروية.

المعادلة الأولى هي قانون جيب التمام المعدل, و الذي يكون مفيداً في بعض الحالات و لكن لا يطلب تذكره و حفظه

المعادلة الثانية تبرز قانون الجيب. و يمكن ترتيب هذه المعادلات كالتالي :

بشكل مشابه,

عادة ما يكتب قانون الجيب بالشكل التالي:

المعادلة الثالثة تعطينا قانون جيب التمام:

و بشكل مشابه نكتب:

cos(c) = cos(a) cos(b) + sin(a) sin(b) cos(C)

و هنا القوانين الثلاثة بشكل نهائي:

يستطيع قانون جيب التمام تقريباً حل مجمل مسائل المثلث الكروي إذا استخدمت بشكل كاف. أما قانون الجيب فحفظه أسهل لكنه غير كاف في العديد من المسائل.

تذكربأن كلا الصيغتين ربما تعانيان من الالتباس في النتائج :

و على سبيل المثالإن كانت نتيجة قانون الجيب

فيمكن ل x أن تكون 30° أو 150° !!.

و ربما نتج عن قانون جيب التمام

عندها تكون قيمة الزاوية x هي 60° أو ربما 300° (-60°). في هذه الحالة لا يكون هناك التباس إن كانت x هي القوس في المثلث, و هو ما يعني أن قيمته أقل من 180°, لكن ربما سيكون هناك شيء من الشك فيما لو كانت قيمة الزاوية للمثلث ذات قيمة موجبة أو سالبة.

لهذه الأسباب, عند تطبيق أي من هذه الصيغ, تأكد من كون النتائج ذات معنى منطقي.و في حال الشك, قم باستخدام صيغ أخرى للتأكد من النتيجة.

تمرين:

مدينة Alderney, في جزر الشانيل ذات إحداثيات

مدينة Winnipeg, الكندية, ذات إحداثياتhas

ما هو البعد بين المدينتين محسوباً بالميل البحري, على طول قوس الدائرة الكبرى؟

إن أردت رسم طريق من مدينة Alderney على الدائرة الكبرى باتجاه مدينة Winnipeg, ففي أي اتجاه عليك التوجه (المقصود باتجاه أي سمت)؟

الحل

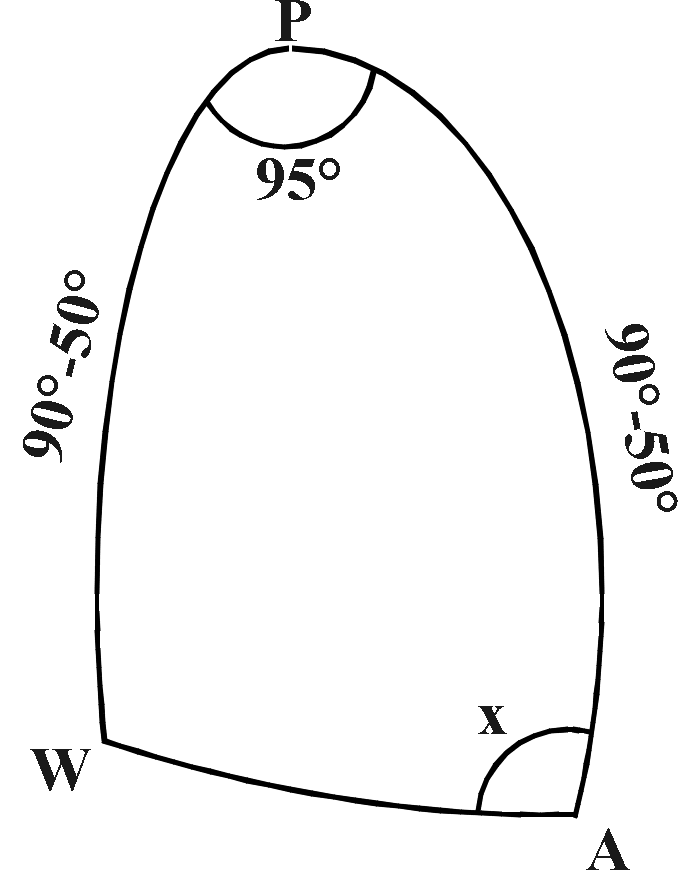

(الشكل-12) المثلث بحسب معطيات التمرين

(الشكل-12) المثلث بحسب معطيات التمرين

= cos240° + sin240° cos 95°

= 0.5508

بالتالي طول القوس يساوي

AW = 56.58°

= 3395 nautical miles

إن أردت رسم طريق من مدينة Alderney على الدائرة الكبرى باتجاه مدينة Winnipeg, ففي أي اتجاه عليك التوجه (المقصود باتجاه أي سمت)؟

سنستخدم قانون الجيب :

بالتالي

sin x = sin 40° sin 95° / sin 56.58° = 0.77

بالتالي

x = 50.1° or 129.9° .

و الاحساس يقودنا إلى 50.1° (أو يمكنك استخدام قانون جيب التمام للقوس PW).

يقاس السمت باتجاه عقارب الساعة بدءاً من الشمال, بالتالي فإن السمت

360° - 50.1° = 309.9° وهو السمت الذي تقع عليه مدينة winnipeg في أفق مدينة alderney. من الواضح انه باتجاه الشمال الغربي.

- الكرة الأرضية

-

ترجمة قتيبة أقرع

- ملاحظات حول الهندسة الكروية

(Figure-10)

(Figure-10)